America’s trucking industry is a central and critical link in the supply chain. With more than 7.6 million employees nationwide – including 3.3 million professional truck drivers – the industry moves 10.23 billion tons of freight annually, or 72.5% of total domestic tonnage shipped in the United States.

As an essential link, truckers feel pressure any time the supply chain gets squeezed. Today, those pressures are felt upstream and down—from diminished factory production in Asia as a result of the Delta variant, to faltering infrastructure here at home following decades of disinvestment by Washington.

Trucking is not the source of these current woes, but we will be a key part of the solution—just as we were through the darkest days of the pandemic. Truckers have been on the frontlines since Day One, delivering PPE, medical supplies, life-saving vaccines, and life’s daily essentials. We persevered through unimaginable hardships to ensure the economy’s wheels kept turning.

Now, as the global supply chain struggles to untangle itself out of the COVID recession, rest assured truckers will continue to have America’s back.

Big Picture: The Global Supply Chain

Understanding the current crisis requires a long lens.

The flow of global commerce depends on a complex and delicate international supply chain. It takes a holistic view to see how a confluence of factors is now causing that chain to buckle.

→ Manufacturing→

Decades ago, large elements of the U.S. manufacturing base began migrating overseas as companies looked to reduce labor costs. It’s from Asia where many of today's pressures are emanating.

As the Delta variant continues its deadly surge, factory output there remains crippled – at about 50% of pre-pandemic levels. High-volume container ports in China, Vietnam, and Malaysia are operating at reduced capacity, with severe downstream effects for American consumers.

China is the largest foreign supplier of goods into the U.S.; we depend on the Chinese for machinery, furniture and bedding, toys and sports equipment, and agricultural products like processed fruits and vegetables. Vietnam and Malaysia provide the U.S. with medical instruments, microchips (a key component in new devices and automobiles), apparel and footwear, and grocery items like pastas, cereals, baked goods, and vegetable oils.

A major reason for delivery delays and empty shelves is that these goods are stuck in Asian factories and ports.

→ Shipping→

The advent of large steel shipping containers enabled globalization by drastically reducing the cost of moving vast quantities of freight over the ocean. Some 90% of globally traded goods move by sea, 60% of which are packed into those crates. That includes virtually all of the imported fruits, smartphones, TVs, kitchen appliances, and other modern marvels that consumers take for granted.

The problem? A global shortage of containers, as crates pile up at coastal and inland ports around the world because of surging demand and a lack of labor. This has driven up the cost of shipping six-fold, contributing to the rising prices consumers see in-store and online.

The ocean shipping industry, comprised almost entirely of foreign owned-companies, has consolidated in recent years into three large alliances. As White House executive order on competitiveness recently noted, this foreign shipping oligopoly poses problems for the American consumer.

→ Ports→

In order for efficient drayage, truckers need access to three things: information, equipment, and space. Currently, there is a lack of all three. Information sharing is extremely disjointed; chassis are unavailable; and there’s no physical space—both in nearby warehouses and portside—for truckers to deliver loads and return empty containers and chassis.

More trucks and longer hours only help if truckers have real-time information to make pickups and returns, have chassis to move containers, and have somewhere to drop freight and return equipment.

🛑 Information Sharing

Information sharing inside major ports is extremely disjointed. Each terminal within a port system have separate information portals. Having no global view of operations makes it difficult for truckers to service multiple terminals throughout a port system. Within a terminal, truckers are given little or no notice as pickup and return availabilities open and close.

🛑 Chassis

Intermodal chassis might be a term unfamiliar to many consumers, but this rudimentary piece of equipment is a critical linchpin of international trade. Chassis are the rolling framework on which a shipping container sits for truckers to haul in and out of ports. Before a truck can pick up a container, they must first pick up a chassis from a provider inside or near the port.

Recent tariffs imposed on Chinese-made chassis have made them prohibitively expensive, and American chassis manufacturers are unable to keep up with demand. Moreover, deeper, systemic issues within the chassis market have hindered the efficient movement of freight for years.

Often times, foreign-owned ocean carriers require truckers to lease chassis from a specific provider which the steamship line has a partnership with. For example, if Trucker John wants to pick up a container from a Red Ocean ship, he must lease a red-colored chassis from Red Chassis Co. – even if no red chassis are readily available, and despite the fact blue chassis are abundantly available. As a result, the container can't move, and the backlogs worsen.

Moreover, after dropping a load at a warehouse or distribution center, Trucker John then has to return that red chassis to its pool, even if it’s located in Terminal A and his next pickup is on the other side of the port in Terminal E. John might wait 40 minutes to get through Terminal A’s gate, only to find that return location is now full, leaving him with an empty chassis that he can’t use to pick-up his next container.

🛑 Detention and Demurrage

All parties in the supply chain should be focused on the common goal of moving freight as safely, efficiently, and cheaply possible for the American consumer. However, this incentive structure is often misaligned, with one example being the practice of detention and demurrage fees.

These charges are levied on motor carriers by ocean carriers when containers are not picked or returned “on time.” The problem is that delays often arise from factors completely outside of truckers’ control. Charges can be levied even though return locations may be unavailable, containers are not yet shown as available for pick up at a terminal, or for days when ports are closed. Imagine trying to return your book to the public library, only to be told “sorry, we have no room for it right now, so you’ll have to continue paying your late fee until we find space.”

Although the Federal Maritime Commission has tried to address this grotesque practice through an interpretive rule, it thus far has had little impact. This system pads the bottom line of foreign-owned ocean carriers at the expense of hardworking American truckers.

The Trucking Link

When trucking stops, America stops.

Truckers aren’t just the backbone of the economy – they are the heartbeat of our nation.

As a central link in the supply chain, America’s trucking industry finds itself caught in the middle of these cascading pressures – from the shuttered factory in Asia, to the backlogged ports, overflowing warehouses, and pothole-lined highways across the U.S. Our ability to move the economy forward and get goods onto store shelves and into the hands of consumers is hindered by this sequence of hurdles.

Like other freight industries, we face our own capacity challenges. The long-term truck driver shortage predates COVID-19 but was exacerbated by the pandemic, as state DMVs and driver training schools closed, cutting off the pipeline of new drivers entering the industry. In 2021, we estimate the industry is roughly 80,000 drivers short of what it needs optimally meet current freight demand.

There is no single cause for the truck driver shortage. Contributing factors include a high average age of current drivers, which leads to a high number of retirements; the fact that females comprise only 7% of all drivers; and the inability of some would-be and current drivers to pass a drug test.

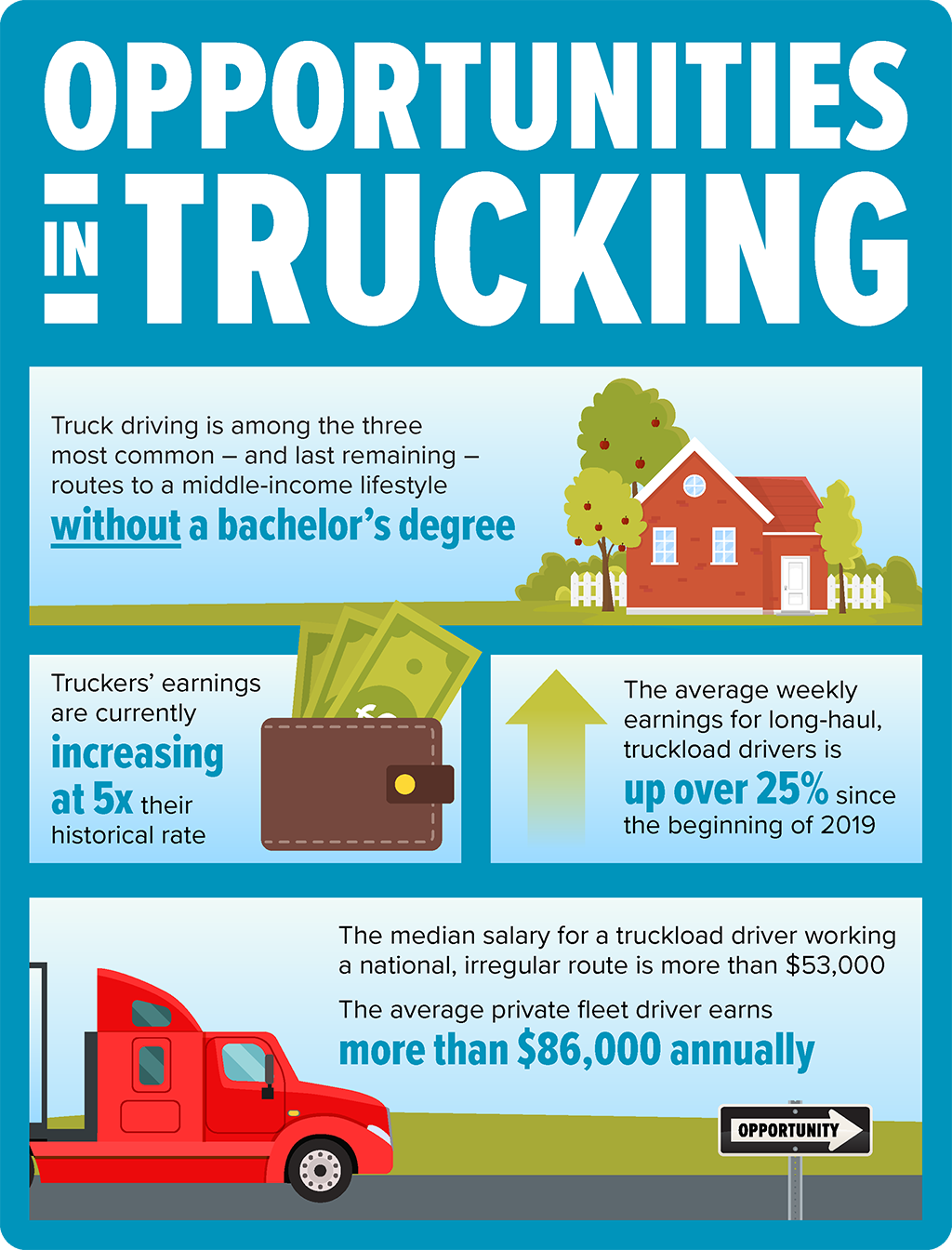

While there is no single cause to the driver shortage, the trucking industry is pursuing a range of solutions to help address the issue. We are in full-on hiring mode: Truckers’ earnings are currently increasing at a rate 5x their historical average, and the average weekly earnings for long-haul, truckload drivers are up more than 25% since the beginning of 2019.

The fact is truck driving is among the three most common – and last remaining – routes to a middle-income lifestyle without requiring a bachelor's degree. The industry has ramped up recruiting in underrepresented communities, including women, urban and minority hiring. We’re building pipelines for exiting military service members to transition into trucking careers. And we’re advocating for new apprenticeship programs that will help prepare and train high school graduates for long-term careers in trucking.

Today, the average age of a new truck driver entering the industry is 35 years old, and the average age of all drivers is 47. As the current workforce ages out and retirements grow in number, it’s critical the industry has the clearance it needs to recruit the next generation of truck driving professionals.

Dos and Don'ts for Policymakers

- DO pass the bipartisan infrastructure bill. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will make long-overdue investments in trade infrastructure. It contains crucial programs to help strengthen trucking’s workforce and grow the number of truck drivers in our economy. There can be no immediate nor lasting solution without passage of IIJA.

- DO promote open, fair and competitive practices in our nation’s ports, including chassis choice and interoperable chassis pools. The chassis market is broken and one of the most significant, overlooked chokepoints gumming up the movement of freight through coastal and inland ports. The current system is designed for inefficiency, profiting foreign-owned ocean carriers at the expense of American truckers and consumers.

- DO pass the Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2021. The current law has not been updated in two decades, during which dramatic changes have occurred in the maritime shipping marketplace. This legislation would strengthen penalties for unfair trade practice and help alleviate bottlenecks by ensuring American truckers, shippers and exporters are no longer at the mercy of foreign-owned ocean carriers.

- DO NOT further disrupt the supply chain with one-size-fits-all vaccine mandates. The forthcoming OSHA rule threatens to fuel truck driver turnover and retirements and could sever a supply chain already in danger of snapping. Truck drivers operate in one of the safest environments for mitigating viral spread – alone and inside a truck cab – and the industry has proven throughout the pandemic that it can operate safely while delivering vaccines, PPE, and critical medical supplies to the frontlines.

- DO NOT enact AB5 or the PRO Act. These state and federal proposals would essentially outlaw independent contracting, decimating truck capacity overnight. Independent contractors are an essential pillar for a viable trucking industry. This is especially true today, as the holiday season nears and surging freight demand is pushing the supply chain to the brink. If not for the AB5 injunction now in place, the crisis playing out in the Ports of LA and Long Beach would be exponentially worse.

Dos and Don'ts for Consumers

DO be patient and plan ahead. Untangling global supply lines won't happen overnight, and we anticipate these challenges will persist into 2022. With the holiday season upon is, it'd be prudent for consumers to anticipate delays and get their shopping done ahead of time.

DO NOT horde. Panic buying solves nothing and adds fuel to the fire by spreading a sense of mass hysteria.